Oh, that river. It lay at the heart of almost all of the work at Grand Canyon, even though it was about a vertical mile below the Park offices.

The Colorado River flows down from Glen Canyon Dam and through the heart of the park, twisting and turning and eventually pulling away all of the eroded rock slowly dumped, bit by bit, pebble by pebble, down the wash of countless side canyons and into its current. It uses the rubble like the teeth of a giant chainsaw to carve through the ancient dense rock of the deepest sections of its riverbed. It is the force that made the spectacle that is Grand Canyon.

I had wanted to get on to the river ever since I saw it on my hike with West Virginia University. I had done a good bit of whitewater rafting on the Youghiogheny River in Pennsylvania and several other rivers in West Virginia before, but this was world class whitewater, and a long, long stretch of it. Not only that but one was traversing through one of the wildest, most beautiful, and yep, most isolated places in the world. If you got in trouble in the heart of Grand Canyon, help was quite a distance away, and in drastic circumstances, ironically depended significantly on helicopters to pull one out of the “ditch.”

Yes, I had wanted to get on the river forever, and then I heard that my number had come up. Joe had finagled a magic ticket. I was to take my surveys and a decibel meter downriver.

At the time, there were two National Park Service resources management trips that headed down the Colorado each year. One was all about archaeological resources; discovering them when possible and surveying those that were known, looking at possible degradation caused by high water, river runners, or other forces that could damage them.

The second trip that ran down the River was focused on natural resources, and took several approaches to determine how they were faring. Our trip was to include several projects; one was a photographer who had copies of historic photos he sought to replicate. He would lug his (big!) camera and tripod up some of the most challenging hillsides, switchbacks, and buttes imaginable to find the exact location where an original photograph might have been taken.

Some of those photos were taken by early survey teams under the direction of Major Powell, the first known person to lead a trip down the river. A one-armed Union soldier, he not only led that first expedition, but also led and championed survey work throughout the west, eventually resulting in the U.S. Geological Survey. He commissioned photographers to record the scenes, and also played a significant role in capturing the ethnographic details of the tribes living in the area, once climbing down into a Hopi kiva to sit in extended – and unclothed – prayer with members of the community.

In preparing to write this, I read The Promise of the Grand Canyon by John F. Ross – a wonderful look at Powell’s legacy. One of my favorite tales spoke of his friendship with another Civil War veteran, who fought for the opposing Confederate Army – and lost the other arm. Throughout his later years, every time Powell bought a set of gloves, he would ship one of them off with a short note to his southern friend – who would return the favor when he purchased gloves. To descend this mighty river with one arm is awe-inspiring.

The photographer on our trip also followed in the footsteps of Ellsworth and Emory Kolb, two brothers who came to the Canyon in the early 1900’s to bring the relatively new field of photography to that incredible landscape. Building a studio at the top of the Bright Angel Trail, the two brothers scrambled and leaped, taking some death-defying photographs while also setting a visual benchmark for all of the changes that were to follow. Their images were just some of the scenes our photographer hoped to reproduce and analyze.

By comparing the photos, he could see how the river might have changed. He could look at trees and tree species, plants and most specifically the sandbars that line the river. One of the more controversial river topics by far was the construction of Glen Canyon Dam and how it had impacted the water flow down the Colorado. When Powell ran the river, it was a churning mass of brown funky stuff. The descriptions reminded me of those I had heard about the Mississippi River; “Too thick to navigate and too thin to plow.” Certainly it would not have been pleasant to drink without filtering or letting it settle for an extensive period of time.

The Glen Canyon Dam had changed all of that, harnessing the power of the Colorado and the water for irrigation. At the same time, it regulated the flows, now heading at much more constant levels over the course of the year. This changed the way that sediment flushed down the river and was washed up along the sides. Sandbars were a big topic of discussion in the Resources Management Division.

Along the same lines, one person on the trip was tasked with climbing above every beach we stopped at and sketching the contours of the sand below; another look at how they’d shifted. That sketch was added to an extensive collection, not quite as old as the Kolb brother’s work but collected routinely in recent years.

I was to join the river trip, already in progress, at Phantom Ranch. I was disappointed that my adventure was not for the full length of the Canyon, but several folks assured me the best stretch of river was west, below the Ranch.

My first task, however, was going with some of the crew over to Lee’s Ferry, the starting point for the river runners, and bringing their car back. We set off very early in the morning, as I recall, and as we swung past the exit of the Park and up the highway across the Little Colorado River and the Painted Desert, I was told to stuff a white pillow into the window ledge above the back seat. I swiftly realized this was to obscure our white General Services Administration logo on the window so we could discreetly burn a joint on our way up to the River. That did nothing for the obvious government license plates, but it did help us slip into “stealth mode.” I knew John would not approve, but when running with river runners…

Lee’s Ferry is one of the few places where it is relatively easy to reach both sides of the Colorado River, and was founded by John Doyle Lee in 1870. A Mormon, he had fled to this remote spot with two wives and some children, hoping to evade capture for participation in a massacre of Arkansas would-be settlers at Mountain Meadows, Utah in 1857. He established a ferry business and lived comfortably in this spot, which he named Lonely Dell, until the law finally caught up with him. He was executed by a Federal firing squad in 1877.

When we got to Lee’s Ferry, now featuring a bridge, the place was humming. Several commercial groups were busy inflating their large rafts, organizing oars and paddles, sorting gear and going through basic safety drills with their clients. Our group consisted of three or four smaller rafts designed to hold about six intrepid explorers each.

Our cook, a marvelous woman who based a lot of her work around a dog-eared paperback copy of The Joy of Cooking, had a beautiful compact kitchen set-up that fit inside just a few coolers and ammo cases.

Everyone was in good spirits and I watched jealously as the team loaded up and finally pushed off the beach and down the river. The first section of the river is really a series of meanders that slowly took them out of sight, into a not very deep section of the Canyon. It was rather open and sun-drenched. I was eager to rejoin them down river at Phantom.

I drove back toward the South Rim, inspired and enthused and hardly able to think about the adventure that lay ahead. I stifled my jealousy with a stop at the Cameron Trading Post, a historic spot along the road back to the Park.

Cameron is a huge store, filled with many beautiful Navajo arts and crafts, mixed in with the inevitable mass of t-shirts and souvenirs. Hats, blankets, case after case of delicious silver and turquoise delights, it was a great place to find something for everyone. There was only one thing I wanted that day – a Navajo Taco.

Navajo Tacos are almost what the name implies; beans and chili and sour cream and lettuce and tomatoes all mounded on top of a large plate-sized round of fry bread. I had discovered this treat on my earlier trip to Arizona, and it never failed to lift my spirits – and the number revealed when I stepped onto a scale. Local rumor had it that the best Navajo Tacos were served at Cameron Trading Post. The recipe I linked to above has a much smaller version, suitable for whetting the appetite. The Cameron version is difficult to consume at one seating.

Back at South Rim Village, I packed and repacked, bought some waterproof gear, and got ready to head down the South Kaibab Trail a few long days later, planning to spend the night at the Ranch and meet them the next day. I was taking NO chances on missing my appointment.

I camped that night at Phantom Ranch, chatting with the Ranger as I thought about what was to come. The sun could not rise soon enough. The next day I could hardly stay away from the beach on the Colorado River, hauling my gear to a shady spot. When the National Park Service boats came into view my heart was racing again. Some of the scientists that had been on the first part of the river trip were leaving, headed back the way I had come up to the South Rim. The river crew stayed on, and it was a good thing. They were the experts, and I was in good hands!

The Park Service recruited folks from the commercial tour operators that ran the Canyon, as well as others, to pull together their river team. These folks knew what they were doing on the water. To think that the Park Service was even paying me extra (per diem) to be on the river! Incredible. After some brief goodbyes along the beach, we pushed off and headed down the River. My guide and oarsman was a tall wiry character nicknamed Big T. He had many years of experience and I was glad to have him pushing and jamming the long oars behind me.

The river crew were a bit wild, which was only to be expected. I remembered the dramatic day when we discussed an “incident” in the resource management office. A Park visitor had been hiking along the top of the Inner Gorge, and had spotted several rafts on a beach far below, emblazoned with the initials NPS. He was a bit stunned to behold one of the female crew drying off after a swim by doing a series of nude cartwheels on the beach. From all reports, the Superintendent took a dim view of this performance.

People come from all over the world to take on the Colorado River. I loved whitewater rafting, but the Colorado was something else altogether. As it passes Phantom Ranch, the River is buried in the heart of the Inner Gorge. While the rock above lies in flat sedimentary layers, down here the geologic forces twisted and folded some of the most ancient minerals exposed on this planet, about 17 billion years old. Vishnu Schist. Zoroaster Granite. Shinumo Quartzite. Cardenas Basalt. These were not sediments any more, laid down over eons. These rocks had been compressed, altered, metamorphosed by incredible pressure and heat deep inside the earth. And in a comparative flicker of time, the River had begun chewing and tearing through their dense layers, exposing their eerie dark beauty.

As we pulled away from Phantom Ranch, the river seemed calm. Small eddies curled at the base of nearby cliffs, which if sun-baked, could radiate substantial heat. Swifts dashed by, scooping insect meals like snacks to go. The placid water reflected the looming cliffs, creating an ethereal double landscape. I perched myself on the fat rubber tube that outlined our craft and, I am sure, grinned like a maniac.

Smaller rapids at Bright Angel and Pipe Creek gave a preview of what was to come. Horn Creek Rapid was a major eye-opener. The adventure had begun!

Thanks to Wikipedia, I’ve mixed a listing of the rapids we encountered with those memories I’ve savoured. I was far too busy hanging on (and grinning) to take notes.

The listing includes some fantastic photography. The number in parentheses is the class of rapid, a rough measure of its challenge. The higher the number, the more likely it is to blow you out of the saddle or flip the entire raft. It is also important to note that as water levels change – controlled entirely by the Glen Canyon Dam outflow, water levels can make a rapid devilish – or completely raise the water level to the point where a rapid becomes a small gurgle in the middle of the river.

- Mile 88.1 – Kaibab Bridge and Phantom Ranch boat beach, where the South Kaibab Trail crosses the river

- Mile 88.3 – Bright Angel Rapid (3), Bright Angel Creek and Bright Angel Bridge, where the River Trail begins

- Mile 89.5 – Pipe Creek Rapid (3), where the River Trail ends and continues towards the South Rim as the Bright Angel Trail

- Mile 90.8 – Horn Creek Rapid (7-9) – At lower water, forms very large waves and hydraulics and is one of the most difficult rapids in the canyon requiring a right to left downstream pull to miss the rocky right shore.

Horn Creek Rapid was one of the first that really got my attention. The noise grew slowly until we pushed over the lip into a tongue of watery chaos of foam and energy. Heart churning lurches and leaps scrambled us as the rubber raft tried to absorb some of the pounding. Our guide, reaching long oars out and twisting, turning, jamming the raft to carve through the mayhem, steered us down to the path of “rooster-tails,” the series of standing waves which gradually dissipates the energy below big rapids.

For anyone but the oarsmen, there is little to do in such circumstances. My job was to hang on and to try not to pop out of the raft. I was used to paddling, and back paddling, and sweeping and all of the other maneuvers that allowed a paddle raft to navigate, following orders from the guide like a coxswain leading a crew team. Now I just had to hang on! Sometimes that was a bit challenging. It was nice to let Big T. make all the lightning decisions and oar sweeps that got us through.

Note the preparation involved in having a ready to go distress signal!

We lazed along that afternoon and finally called a halt as the sun was beginning to disappear. Of course in the Inner Canyon, it disappears pretty quickly and darkness sets in with a vengeance. We found a beautiful sandy beach and I was in love with this experience already. This was to be the first of five nights camping in soft sand, with the river providing a constant lullaby.

The cook got out all of her gear, and began to fix a taco feast. She looked over at me and smiled. “These are Bill Jones tacos!” I told her I had never heard of those; I don’t believe the recipe was in my Mother’s Joy of Cooking. She laughed and said “No, they’re not. You get a taco shell and then you “Bill Jones.” I got it.

As far as the toilet facilities were concerned, we were to perch on the “Throne,” an old ammunition can with a wooden seat. The can was lined with plastic bags, and waste was treated with a chemical to ease the odor and begin the breakdown process. In the morning, the bag was tied off and covered by another bag, layering up as the trip went on.

However, when one had to urinate, that was straight into the river! Apparently, many people had complained about sleeping on urine-soaked sands by the side of the river as folks tried to avoid pissing into the largest flush toilet in the world. It was decided (in a series of public meetings) that the best solution to this problem was dilution.

This lovely isolation was to be our home for the next six days. No phone, but this was long before the days of cell phones anyway. No television. No newspapers. No radio. Except the very crackly one that would occasionally be able to pull in a signal from the rim. We were on our own, and I could not have been happier about it. This news addict went cold turkey!

I set up my sleeping bag behind some Tamarisks. They are a small tree, and an invasive species, one of the larger resource management challenges along the River. I did not need a tent, preferring to sleep staring up at the thin trail of stars visible between the Canyon walls as long as I could keep my eyes open. With virtually no light pollution, Grand Canyon is perhaps the ULTIMATE Dark Sky country. One could see the heavens dappled with countless stars. I contend that everyone should visit a place regularly where it is possible to see at least a trillion stars. Does it get any better? I don’t think so.

I was warned about Ringtail Raceways, though, by some of the seasoned souls. Set up camp in some sections of the beach and the small rascals, mammals with wide anime eyes and a fluffy striped tail, would drive one a bit mad by dawn. This was their territory, after all! As Wikipedia states, there is an additional reason to avoid their paths. “The musky smell they excrete deters would be predators such as foxes, coyotes, and bobcats.”

- Mile 93.1 – Salt Creek Rapid (3)

- Mile 93.9 – Granite Rapid (7-8) – One of the more difficult rapids with a strong push of hydraulics to the wall on river right.

- Mile 95.5 – Hermit Rapid (7-8) – Perhaps the strongest hydraulics and biggest waves in the canyon; terminus of the Hermit Trail

- Mile 97.1 – Boucher Rapid (4-5)

- Mile 98.2 – Crystal Rapid (7-10) – [1] Several very large holes followed by a dangerous rock garden at bottom of rapids on river left. Formed in 1966 when a flash flood of Crystal Canyon washed debris into the river. The beginning of a series of rapids called “the gems.”

The next few days we drifted along, the day’s quiet progress down the river interspersed with the grumbling and rumbling of countless minor rapids, and a few monsters. We would generally stop and scope things out before actually taking on the larger rapids. Our guides would watch as the commercial groups, some with rafts so large that they could almost cover the entire churning mass of waves, took on the rapids. Kayaking looked somewhat insane, but there were usually a few folks with nerves of steel and scuffed helmets accompanying the tour groups.

We hit Crystal and a number of other major rapids. Every time a stream came rushing down a side canyon into the river it seemed to bring rocks and debris with it, creating a rapid. As we heard a churning in front of us, we would survey what lay before us. Big T. would point out the path we would run, the rocks we wanted to avoid (please) and the turns and twists we would have to make to safely navigate the mass of churning foam. I learned a lot, but I know there is still a lot more I could learn about running rivers.

One of the most dangerous situations on the river is deceptively called “pillowing”. Rafts can be trapped against a rock, with what seems to be the entire hydraulic force of the river plastering it into place. Sadly, rafts are not the only items that can suffer this fate. We swiftly learned the command to “High Side,” jumping into the upper end of the raft to prevent a flip and possible pillowing against a river rock.

- Mile 99.7 – Tuna Creek Rapid (5-7)

- Mile 100.0 – Lower Tuna (Willie’s Necktie) Rapid (4)

- Mile 101.1 – Agate Rapid (3)

- Mile 101.8 – Sapphire Rapid (6)

- Mile 102.6 – Turquoise Rapid (2-4)

- Mile 104.5 – 104 Mile (Emerald) Rapid (5)

- Mile 105.2 – Ruby Rapid (4-5)

- Mile 106.5 – Serpentine Rapid (6-7)

One night we stopped at a beautiful beach that was almost completely set inside an incredible rock alcove. If you imagine a large concert hall, it could have not had better acoustics. Sheltered from the elements, I wished we could have a good thunderstorm to put the shelter to a test. A philharmonic orchestra would have looked right at home.

Late that night, being unable to sleep (maybe it was those Ringtails?) I took a small trail up the side of the river and hiked to the beach I had seen just a minute or two before we had pulled in. My private beach! I arrived there just as the moon was poking its head above the Canyon walls above. I stripped off all my clothes. I stifled a yelp of pure joy. And then, after a brief dip in the frigid waters, I turned cartwheels in the dark to dry off in the warm luscious night.

We were not there just for fun, however. There was work to be done and when we got to a new beach survey teams went out to map the sandbars from above. I helped the photographer lug the tripod and his heavy camera case up some hills to recreate that historic shot. We looked at Tamarisk invasions, and tried to focus on work. It wasn’t always easy!

- Mile 108.3 – Beach and trailhead for the South Bass Trail.

- Mile 108.4 – Bass Rapid (3)

- Mile 109.3 – Shinumo Rapid (2-3)

- Mile 109.6 – 109 Mile Rapid (2) This sleeper of a rapid has sharp schist fins on river right.

- Mile 110.0 – 110 Mile Rapid (2-3)

- Mile 111.4 – Hakatai Rapid (2-3)

- Mile 112.8 – Walthenberg Rapid (3-6)

- Mile 113.6 – 113 Mile Rock (2)

- Mile 117.2 – Elves Chasm– A popular side canyon with a small clear-flowing stream with waterfalls and multiple pools.

I had a bit of down time one lovely afternoon. The team was off on various research junkets, and since we were in an area where a number of the commercial tours stopped, I took the opportunity to try for a few more surveys. I found a spot in the shade next to a delightful and busily babbling brook. I had a paperback book (always) and read a few pages (second page, third time) before my eyelids started to lower.

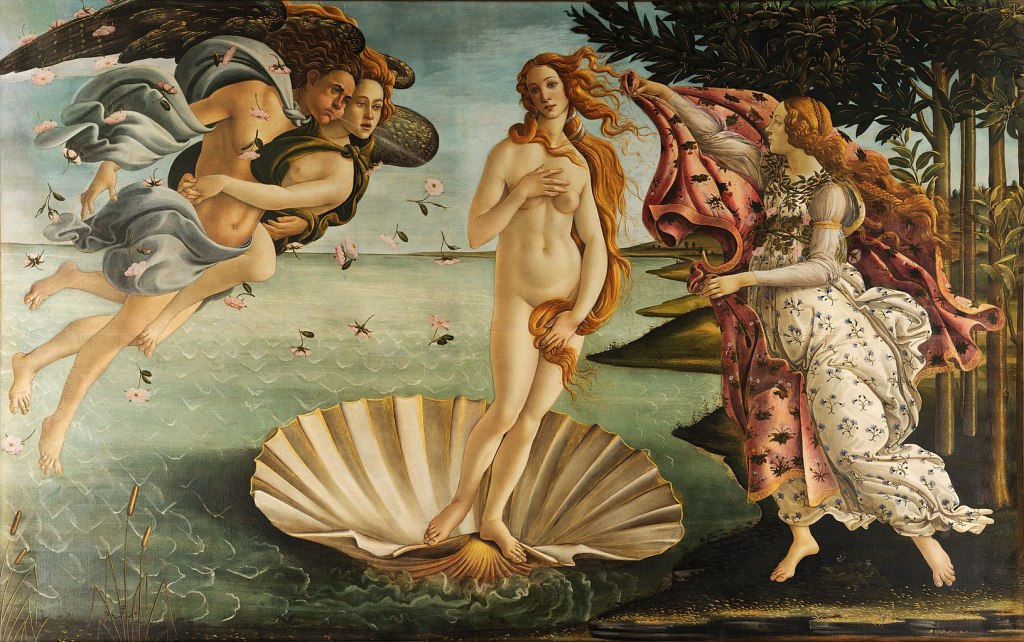

They popped open in a heartbeat. There, before my startled eyes, was a vision of loveliness. Tall, beautiful, statuesque, with long blond hair draped around her form, a Venus rising from the stream. And dressed, like Botticelli’s, only in her long hair and a few transparent streams of water. My heart may have skipped several of those beats. I was transfixed as she caught sight of this stunned researcher (If I hadn’t been speechless, I might have maybe stammered “Survey, ma’am?”) gazing in admiration. She laughed, a lovely sound that the stream could not compete with.

And then, behind her, rose Adonis, similarly attired and just as amused by my startled response. They dashed upstream, splashing and celebrating the day. It took me a while to recover.

- Mile 119.3 – 119 Mile Rapid (2)

- Mile 120.6 – Blacktail Rapid (3)

- Mile 122.2 – Mile 122 Rapid (4)

- Mile 123.3 – Forster Rapid (3-6)

- Mile 125.5 – Fossil Rapid (3-6)

- Mile 127.5 – 127 Mile Rapid (3)

- Mile 129.2 – 128 Mile Rapid (4)

- Mile 129.7 – Specter Rapid (6)

- Mile 131.1 – Bedrock Rapid (6-8) – The river splits around a very large rock outcropping. Going left of the rock is not recommended.

- Mile 132.3 – Deubendorff Rapid (5-8) – Has multiple large holes and pourovers on the left and center

There was a cave along our route, and some of the group were tasked with checking how it was faring. I eagerly joined the team and we headed up a stream that disappeared into the wall of the side canyon. We turned on lights and walked along narrow ledges, hugging the walls for a while, and admiring the stream – until we had no choice but to start wading up the middle of the flow. We had good lights, but after a while the walls started closing in, the ceiling to descend, and the water climbed up our legs toward waistlines. After a stretch of stoop-walking, the decision was made to turn around. I thought it was a good idea at the time.

- Mile 134.3 – Tapeats Creek – A large creek entering at river right. A popular hike up Tapeats Creek leads to Thunder River.

- Mile 134.3 – Tapeats Rapid (4-5)

- Mile 135.4 – 135 Mile (Helicopter Eddy) Rapid (3)

- Mile 135.6 – Granite Narrows. This is the narrowest location of the river at 76 feet.

- Mile 136.9 – Deer Creek Falls – A popular stop, both for the falls themselves and for hikes up to the “narrows” and the “throne room.”

- Mile 138.4 – Doris Rapid (4)

- Mile 139.2 – 138.5 Mile Rapid (3)

- Mile 139.7 – Fishtail Rapid (4)

- Mile 141.7 – 141 Mile Rapid (2)

- Mile 144.0 – Kanab Rapid (2-5)

- Mile 148.4 – Matkatamiba Rapid (2)

- Matkatamiba Canyon is a popular, short hike up a narrow, winding slot canyon with a perennial stream.

One day, we arrived at Matkatamiba Canyon. I had really no idea what to expect, but they had been using the name (or just “Matkat”) on the way down the river, as somehow teasing “Just you wait!”

We started up a pretty normal looking side canyon, with a lovely stream. Soon the walls closed in; large sculptured limestone sides, with streaks of minerals and other details captured in the stone. The water had carved the canyon walls into fantastic shapes, swirls, folds, a sheet of pure stone fantasy spun out on both sides.

This narrow slot canyon occasionally provides glimpses of the sky overhead, but scrambling up the stream, one had to ascend small waterfalls and bridge across the walls at times to continue climbing. It is a magnificent stone cathedral, surreal in so many respects. I would hate to be down in there if a cloudburst of rain dropped upstream. I could not believe a place like this really existed. I wanted to hike further and deeper, but that’s not the way it worked.

- Mile 150.2 – Upset Rapid (7-8)

- Mile 154.0 – Sinyala Rapid (1-2)

- Mile 157.3 – Havasu Canyon is a beautiful turquoise-watered side canyon. Havasu Canyon Rapid (2-4) follows shortly downstream.

- Mile 165.0 – 164 Mile Rapid (2)

- Mile 167.0 – National Rapid (2)

- Mile 168.5 – Fern Glen Rapid (2)

- Mile 171.9 – Gateway Rapid (3)

We were approaching Lava. It’s a spot where lava flows have actually drizzled over the canyon walls and slid down into the river, causing a bit of a backup for a while, as you can well imagine, but certainly something that eventually the mighty Colorado had surmounted. But it left this little rapid. Okay, not so little, a bad boy.

Lava isn’t long, but has got some nasty twists and turns. I was excited, and I gripped hold of that raft, and I stared downstream at the fury. I was pumped. I was ready to go.

I turned to smile at Big T., and he looked down from his oars. I noticed a quick flash of pure panic. “Your jacket!” he yelled, just as the thunder of crashing water started to drown out everything. I had neglected to clip shut the life jacket that I was wearing casually after our inspection stop on the side of the river, above Lava’s fury. I clamped the jacket on firmly. Bet he never makes that mistake again!

- Mile 179.7 – Lava Falls Rapid (8-10) – Also known as Vulcan Rapid, is perhaps the most difficult, if short, run in the entire canyon.[4]

- Mile 180.1 – Lower Lava Rapid (3-4)

- Mile 186.0 – 185 Mile Rapid (2)

- Mile 187.4 – Whitmore Helipad is where most concessions passengers end their trip by helicopter take-out.

- Mile 188.3 – Whitmore Rapid (2-3)

- Mile 205.6 – 205 Mile (Kolb) Rapid (3-6)

- Mile 209.2 – 209 Mile Rapid (3) This rapid has a large hole in the middle of the rapid.

- Mile 212.5 – Little Bastard (LB) Rapid (3)

- Mile 213.3 – Pumpkin Spring

- Mile 216.0 – Three Springs Rapid (2)

- Mile 217.8 – 217 Mile Rapid (4-5)

- Mile 219.6 – Trail Canyon (Ducky Eater) Rapid (2) Cross-river hydraulics can flip small inflatable kayaks here.

- Mile 220.7 – Granite Spring Rapid (2)

- Mile 223.7 – 224 Mile Rapid (3)

- Mile 225.9 – Diamond Creek Take-out. This is the first location downriver from Lee’s Ferry where a road reaches the Colorado River. The road is prone to flash flood by Diamond Creek in monsoon season. This is the only takeout for Grand Canyon boating trips above Lake Mead when the lake is high, however, recently the lake has been lower, giving boaters an easy rider with current all the way to Pearce Ferry.

I survived Lava, and quite a number of rapids after that. We slowly climbed out of the rocks that designated the inner gorge back to sand and limestone layer cake, but it was still so beautiful and I didn’t want to leave. I didn’t want this trip to ever end; it was so fantastic, and then – it was over.

With a heavy heart I was loading up a truck with the rafts, releasing the air valves and watching them starting to look as forlorn and flattened as I felt, riding back to the Park. What a dream!