He promised me earrings, but he only pierced my ears.

Arabian saying

Life involves some suffering.

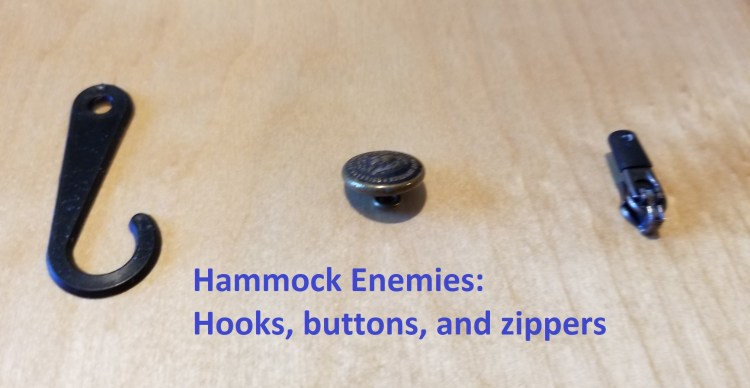

Hammocks have several enemies, the most insidious being buttons, zippers, hooks, and Velcro. If there is a way they can rub against the hammock, cords from the hammock will wrap around buttons, lodge in zippers, and snag on hooks. It seems that there is almost a magical ability for the hammock to get caught on anything possible if it comes within striking distance.

Placing a pad or blanket underneath will diminish the possibility of such dangers. Note that with all of the hooks and clips overhead, invariably things will get hooked sooner or later. And of course, wrapping the end loops with medical tape – the stretchy kind – will help to preserve the cords inside.

Velcro has a different, though similar, danger to the hammock cords. The tiny hooks embed in the cords and start tearing chunks away. Sooner or later – failure.

One evening while sitting in a hammock by the bank of a lovely alpine lake. I hopped out and started climbing up the bank, suddenly realizing there was a tug from behind, pulling me back to the hammock. No, it was not an unconscious desire. A cord had connected to a zippered pocket and was being pulled out of the hammock weave.

Carefully, slowly, disconnect the cord and by gently tugging, pulling, stretching and otherwise manipulating the hammock, pull the cord back into place. No major harm done, but oh so annoying!

At times, a cord will break – hopefully just one. Carefully, gently, try to get out of the hammock without placing further strain on the damaged cord. Once out, do your best to weave the two ends back into place (your chance to try your hand at double sprang weaving). Pull a little extra and connect the ends in a good solid knot (or two). If it is a little tight, that is OK. Sooner or later, the cords will adjust and no harm will be done.

A specific danger I face routinely is bottle caps. If they land “teeth down” in the hammock and slide underneath you, it is only a matter of time before they chew their way through the weave. My solution is to pitch them swiftly over the edge, where they join my substantial bottle cap collection below the hammock.

An interesting point of view is captured in David Bromberg’s admonition “A man should never gamble more than he can stand to lose.” Never string a hammock higher than you would want to fall. It has not happened to me for years, but sooner or later you will misjudge the strength of a branch (maybe insects chose it first) and down will fall hammock, baby and all.

I buttoned myself into the hammock today. I guess the good news is it has taken quite a while for it to occur.. I was wearing a fisherman’s sun shirt with button-up sleeves. Trapped. I guess I could have just yanked it and popped the button loose underneath me, to fall in between a million bottle caps and perhaps disappear. It took quite a while to figure out exactly which set of threads needed to be tweaked apart to free my arm. I finally found the magic combination. Thankfully.

One of my oldest hammocks, the indoor model next to my bed, is about 20 years old. While a delightful model with ultra-thin weave and great comfort, I found that over time the area where I was placing my feet suffered from what I named “weave rot.” Note that the strings did not break, and the hammock is still functional, but it has taken on a religious holiness. You can see the result below.

I have resolved the problem by reversing the hammock, so that this zone is behind my head, and I use cushions and pads so as to not aggravate the problem. One can grasp the edge of the hammock and tug and pull and stretch and the weave will eventually move to a more uniform arrangement, but the “rot” seems to persist. Does this mean it is approaching its lifespan? Sniff! Sob!

Hammocks get old. I was discussing them with a friend, and she told me about her hammock. Repaired multiple times, a comfortable old friend. I was amazed it could still support her. She kindly allowed me to photo-document. When your hammock starts looking like this, it might be telling you time for a new hammock, but what a beautiful old friend. It is rather amazing the way the ends twist, almost like tiny springs.

External Dangers

There are dangers to the hammock, but there are other EXTERNAL dangers which lurk in the forest!

When tying up to a tree branch, never look straight up, as the act of putting the anchor rope around or over, as mentioned elsewhere, is quite possibly going to dislodge things you will not want in your eye or mouth. Stand to the side and sneak a glance at the operation.

If you happen to be in northeastern Australia, beware the Stinging Gympie. Known formally as Dendrocnide moroides, this rascal can inject a painful neurotoxin.

As you take to the wilderness, other plants can pose a threat. Please learn to recognize poison oak, ivy, sumac and other plants which will seek revenge for any disturbance to their habitat. Finding two nicely spaced trees is simply not enough.

Often Poison Ivy leaves will develop a distinct reddish hue, especially in the fall, but in the spring, they glow green. They often have dentition, one or more notches, on the outsides of leaves.

Poison Ivy is particularly insidious because it loves to climb the trees, with a set of vines that also carry the poison. Here, thanks to Wikipedia, is a “hairy” P.I. vine. Be aware that even during the cold winter months, Poison Ivy can still be an irritant – and much harder to spot!

Poison Oak is a small shrub you are more likely to encounter on the west coast, though there are eastern varieties. You are more likely to encounter it when wading into a thicket to get to larger hammock trees.

Poison Sumac is largely found in the eastern sections of the U.S.

I was once on a canoe trip with the Boy Scouts at the Boundary Waters. We were getting ready to portage, and our guide pointed to a small path that climbed up from the beach into the forest. Poison Ivy loves the “edge” of forests – just a bit of shade and a bit of sun. Both sides of the trail were loaded. I pointed out the need for caution, and he stared at me with wonder. “That’s not Poison Ivy!”

As one who grew up in the woods, and has a radar very finely attuned to the plant, I begged to differ. I warned my scouts and let him take his chances.

One of the greatest “slings” of my life happened on that trip. The group settled in to camp on a small island, and just off one shore was a mini-island, connected by a single log bridge. Lo and behold, there were two trees on the mini-island at the perfect distance. Nothing says to a scout “don’t bug me” like a private island!