There are two kinds of people; those who finish what they start and so on.

Robert Byrne

I’ll cut to the chase; if you do not own one, I would recommend that you go and purchase a large Mayan hammock right now. Yesterday. The folks in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula classify them by size, the largest being an 8. That is ALMOST too large, but better if you plan to share extensively. From my experience, the larger number does not mean that the hammock is any longer, end to end, but wider in the bed. The sizes are described in such varying ways on-line (single, double, family, extended family, family and friends, etc.) that these terms are relatively meaningless.

They are available online, and if you can find a “Fair Trade” site it is strongly recommended. Hopefully, they pay the weavers enough to support their families and live a good life. I have included a list of options I have used in the section on Hammock Sourcing.

I prefer cotton, but nylon hammocks are also available. The header cords at the ends are almost always nylon anyway. Cotton does not hold up as well in the “elements” but is generally considered more comfortable. Some come with an elaborate fringe, but to my way of thinking, it is putting mascara on a mustang. These are typically known as “matrimonial” hammocks.

From one of my favorite shows, Death in Paradise, a magnificent matrimonial hammock.

I think the hammock should be Mayan, preferably produced in the Yucatan Peninsula, but they are a big “nation.” The town of Merida seems to be ground zero for the hammock trade. This is, scientists say, also very near another ground zero; the location where an asteroid slammed into the Earth, putting an end to the age of dinosaurs. Coincidence? Perhaps not.

My bro-in-law,* and favorite rodeo author, suggested that this connection demanded a bit more research, skeptical of the relationship. I replied that an impact of this magnitude would certainly have left many sharp rocks strewn about the landscape (not to mention one hell of a dent in the planetary crust), and that one might reasonably wish to rest above this asteroidal rubble. That, in addition to a significant population of things that make their living creeping across the floor at night, could explain why hammocks achieved such local popularity. While none of this is definitive, the asteroid/hammock proximity is extremely suggestive.

*Thad’s tales are a tremendous read.

Yes, they might make hammocks elsewhere, but for traditional hammock weavers of the region, fair trade for their beautiful creations is important. You will be contributing to preservation of the magnificent crafts of an indigenous people.

According to Wikipedia, Columbus was one of the first explorers to document the use of woven hammocks among the Taino people in the Bahamas. The hamaca was also the name of the plant that produced fibers that could be woven into these beds. The name refers to a fishing net of the time. One can almost imagine a fisherman hanging his nets to dry and thinking “Now, that would be a nice place to take a nap.”

I have not been to that part of Mexico myself, Cabo San Lucas and a few border towns being the extent of my experience. From research on the internet, hammock production seems to be largely a family affair, and a cottage industry. Chickens and children are frequently underfoot. Cords are dropped off by the middlemen, and weavers begin to fill the large vertical pole looms. It looks tedious in the extreme, but the result is delightful.

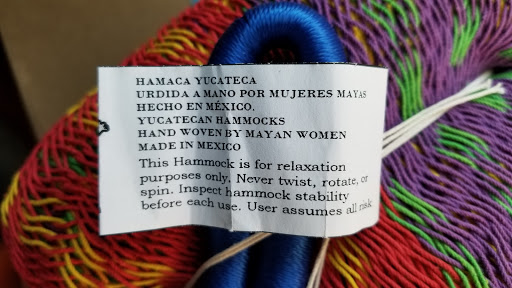

Specialists then whip up the nylon header cords and finish it off, ready to be collected by the middlemen when all is finished. It appears there is a gender-based (or husband ordained) division of labor here, but I have not independently verified that fact. The following hammock tag does seem to confirm the suspicion.

I once suggested to one of the online sellers that weavers enclose a card, with their name and an opportunity to reach out and “tip” them for the wonderful crafts they make. He did not seem terribly enthused with this suggestion.

My last hammock was ordered from a site that offered an opportunity to select the colors. I was trying for a camouflage scheme (they do not have gray or brown cord anywhere in the region, apparently.)

When the hammock arrived, I was surprised that the cords were about three times thicker than I had ever seen before. The hammock is solid, maybe not quite as comfortable as the thin cord, but quite serviceable. If there is any question, though, you may want to check on the cord thickness when placing the order!

They told me that because it was custom-woven, they use the thicker strands to complete the weaving in a timely manner. They assured me that if I wanted to design another, they would gladly arrange to have it woven from the thinner cords.

Update! Washing this big guy produced massive amounts of green dye, and made it about twice as effective as camouflage.

In the photo above, you can see the tan-colored medical tape I wrapped around the end-loops to provide some protection to this area of wear and tear. This hammock also came with what I can only describe as “sacrifice cords,” two small lengths of braided cord that wrap around the end loops and theoretically further protect the actual loops from some level of strain. They appear a slightly brighter color in the photo above. I’ll let you know in a few years how that goes!

You could go wild and purchase three hammocks; one for the Great Backyard, one for indoors, and one for the road. But that’s just me; a wee bit wild. You will find sections in the following narrative describing all three options.

I like the rainbow look, with beautiful hues, when I am not going undercover. They do come in many color choices. Just not gray or brown, I guess.

I do not like spreader bars, which are the problematic sticks at each end of the bed of many of the traditional “American” hammocks. They are truly the cause of the wobbly reputation hammocks have received over the years. Spreader bars keep one from being encased like a human taco; they push the sides out so you don’t feel the claustrophobia of British seamen. A seaman’s shoulders were their spreader bars, and the result looks mighty uncomfortable. Of course, without spreader bars, hammock scenes from Tom and Jerry cartoons would never be the same.

If you’ve seen the movie Master and Commander with Russell Crowe, you saw that hammocks reinforced a class system. The sailor’s hammock was just a chunk of canvas with cords, known as clews, at each end. Rats chewed on it in their spare time. Like almost all hammocks, it could be swiftly cleared for action. “Stow that and grab a cannon!”

“Ye’er not the first sailor I’ve asked to get a clew!”

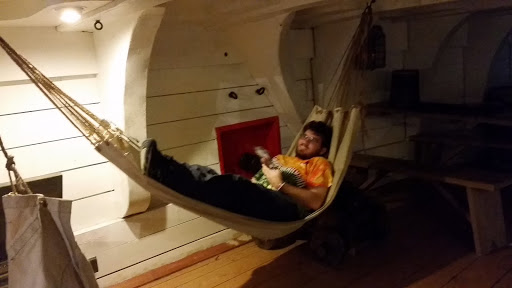

The Captain, on the other hand, got a boxy arrangement with corners and a reinforced floor – it would be closer to a swaying cradle. Either rig made the churning seas a lot easier to stomach, but I would be willing to bet that the Captain got a better rest. The model below was seen at Mystic Seaport, Connecticut, one of my favorite haunts.

The British seaman’s hammock served a dual purpose; at the appropriate time it was used as the sailor’s shroud. And the final stitch through…ewwwck. Sorry – they did want to confirm that the sailor was truly beyond this vale of tears. I’ll try to keep this G-rated. See movie for details. While traditional hammocks often need spreader bars to be truly comfortable, Mayan hammocks don’t. You are the spreader bar. This is not as uncomfortable as it sounds.

Most of these colorful works of art take quite a while to weave. I’ve seen estimates between three days and three weeks. I believe the longer time is more accurate. The most common weaving technique is called double sprang. The cords go under two, over two, and back again throughout the weave.

While you await the hammock’s arrival, you can read this book. I’ve designed it to make the most of the time you spend waiting to “sling out.”

The first item I need to mention is WHERE to sling it. You will need two points of attachment (more on this later) about 10 feet apart, or 3.04 meters. That is about six of my paces. If you are attaching to the house, either indoors or outdoors, large hooks work well, although eye bolts or screws can also be used. Make sure they are carefully screwed into the center of a solid beam or joist, or bolted through. I recommend drilling a pilot hole if you are screwing hardware into a joist.

Hammocks should be connected in the ceiling or almost as high as you can reach, if you are a 6 foot person. A bit higher, like an eave, is fine, although you may need to increase the width a bit to get the right drape.

If you are shorter, you may want to use a small step-stool at each end to set things up. You can always use webbing or rope to make the ends a bit easier to clip up and take down. The key is two good solid points of attachment!

You can also mount some posts in the ground, or connect to a very sturdy fence. I set up a post for the side yard, and angled it about five degrees to reduce the strain of taking the hammock’s weight.

You can always use the traditional tree, of course. I prefer to connect to branches, if big enough, as opposed to the trunk. If a tree has the bark skinned off all the way around the trunk by a hammock cord (girdling), it is a dead tree. It is deeply troubling to me that so many thin hammock straps leave two dying trees in their wake!

I use large one-inch webbing straps, some left over from my distant rock-climbing days, and the heavy-duty climbing caribiners, which usually run about six dollars each. One can also use large links from a hardware store; they are slightly cheaper but do not have as smooth an action in opening the gate.

My first long-term outdoor hammock featured an Ash tree which eventually grew and completely engulfed my webbing. It might be a good idea to reposition or adjust the straps about once a year.

Trees can suffer any number of weaknesses that may be hard to recognize but bring you down, literally. You don’t have to be a forestry major (moi?) but be observant when you select a tree or limb. Insects and disease can hollow out or weaken even the strongest looking branches.

You will probably be looking upward to attach the strap in a tree. Don’t, as you may get a nasty faceful of tree debris. Always try to stand off to the side, or squint, or both. I usually have a caribiner at one end of the webbing to provide some weight to toss over a branch.

The one-inch webbing helps to protect the trees, but I usually take it a step further by adding foam rings made by wrapping duct tape around a swim noodle and sawing off the “doughnuts” (Homer would be proud). These rings can be moved along the webbing to space around the branch or trunk and protect the bark.

Note to self from later field studies. Foam noodles crumble and shed microplastics galore as they age. There has to be a better way to protect trees!

Webbing is incredibly strong and yet because it is wide like a ribbon, it helps protect the trees. I have been doubling the webbing over and tying a knot every few inches, leaving one side just a bit longer. This ladder-knot allows one to clip in at many different locations, increasing the flexibility of the whole set up. It uses a lot of webbing, but makes the sling connections quite flexible.

Here is what that webbing strap looks like, with ladder knots.

Finally, here is a photo of my “road kit.” The green straps have Homers, while the purple straps (used for fencing and non-living connections) just have the knots. They can be used together for the really BIG trees, which probably have fairly thick bark, anyway. The blue bag holds the hammock, while the small tan one holds small clips and the overhead or side cords. I also pack sunscreen just in case the shade is limited. Just add a cold beverage of your choice!

Webbing is pretty amazing stuff. Climbers wrap it around themselves to prevent plunging to their deaths, but it has many other uses.

A friend and I had gone out near Cooper’s Rock, close to West Virginia University, one fine day to do some climbing. We had taken some ropes and other climbing paraphernalia. After some bouldering and repel fun, we headed out in his tiny car, a beat-up Gremlin as I recall. On our way back to the main road, a mud puddle became a bog, and the Gremlin was hopelessly sucked in. We tried several means to free it, but it seemed it just was not happening that afternoon, and the shadows grew longer.

All of a sudden, a cluster of 4×4’s showed up and the burly crew inside burst out, confronting us. Spotlights shattered the dusk. This was a huntin’ club, and we were trespassing! We pointed out that as soon as we could free our chariot, we would be gone. The mountain men (conjuring images of the film Deliverance and sound of a distant banjo) looked at the Gremlin and guffawed.

They said they did not have any chains, and it looked like our chariot was going to be donated to the club (probably for target practice). However, as it was plumb in the middle of one of their dang access roads (bogs) they were as interested in freeing it as we were.

My friend Paul pulled out a long length of webbing we had been using for the climbing exercises. The boys just laughed at the nylon “ribbon” and the Gremlin, at this point mired to the axles.

Paul convinced them that if they tied up the webbing to one of their trucks and gave a wee tug, we would be out of there in no time. More laughter ensued. After a Budweiser or two, and watching us push and pull to no avail, they agreed to give it a try. Soon, as a “giant sucking sound” emerged from the bog, the Gremlin eased its way forward and two muddy, weary, grateful figures climbed in to resume our escape. The “boys” stared in amazement at the “little ribbon that could.” I later learned that the basic tubular webbing strength was rated at about 4,000 pounds. This is probably overkill for a hammock and any number of occupants.

When situating an outdoor hammock, I prefer some shade, but sun-worshipers can go their own way. I have made a “roof” with clear plastic in the past, so that the resulting space underneath is light and airy, but over time have switched to Coolaroo awnings and/or tarps. I have a light tarp I keep in the car to shade any road slings that have insufficient shade, useful when son is playing tennis and the only place to secure the hammock is a chain-link fence.

One important caution! Never leave a hammock outside overnight. At heart, a hammock is a massive blob of string, either cotton or nylon. If you leave it out, rain, dew, and other droppings from a tree or critter will render it unusable in months. All too soon! I stretched out one afternoon and my feet plunged through the side of the hammock – trauma! If you bring your hammock in and out of the elements, or sling it indoors, it will last a very long time. I have one hammock by my bedside that is over twenty years old.

I left an old, small hammock outside (in a rice sack), and now it is occupied!

When taking the hammock down, ALWAYS lock the ends together. This will save you all manner of tangles and pain. I generally twist mine into a more or less compact bundle, easier to stuff in a sack or carry indoors. I pretend it is a giant lasso, like Will Rogers, and spin it around until it twists. Quickly grab the bottom and you can stuff it into a storage sack.

Take care of your hammock, and it will serve you well.

If you are waiting for that hammock to arrive, I will whet your appetite with what you should expect.