A lot of younger folks (am I supposed to refer to them as whippersnappers?) don’t realize how quickly the information age blossomed. I was at Grand Canyon back in 1983-1984. E-mail did not exist – except perhaps within specific organizations. Networks were almost non-existent except for those hooked to gigantic mainframe systems, almost all at large institutions. I had worked with mainframe systems both at West Virginia University and Texas A&M but I can tell you that they were pretty kludgy systems that did not provide a great number of benefits at the time. I learned to program with punch cards. One day I dropped an entire card deck on a rainy West Virginia street corner. My tears may have moistened them further.

The Internet was a glimmer in Vint Cerf’s eye.

Texas A&M had dumb terminals that allowed one to enter information, but were not very adept at handling it well or doing incredible things with it except for mass number crunching. I had my Tandy Radio Shack computer and I was able to write some simple code in Basic when I came to the Canyon, but that was about all we had. The Park had a small system, a “minicomputer” as opposed to the later “microcomputers,” and an Information Manager, but they handled payroll and finances for the Park, and not much else.

Back at Texas A&M, that IBM Personal Computer had arrived at the Marine Lab, but people were still trying to figure out what all the pieces were. The mainframe system was so ridiculous when it came to word processing that everybody was delighted with any improvement in that field. Floppy disks were at a premium. 360K, and then we had to pay several dollars for each floppy disk. It was the dawning of a new day, but things were still pretty dim. Mice were furry things that infested trailers, weren’t they?

With John out dealing with the aneurysm, and while I had never heard of this medical challenge, it was clearly a dangerous condition requiring immediate attention. I was on my own for a while.

As John had received one of the new IBM PC’s and kindly unboxed it all (it was a part of his resources management training program), I decided to get it up and running. He was expected to swiftly become an expert on word processing, data management, and geographic information systems. It was a big ask. His hospitalization gave me the opportunity to get acquainted with his new toy.

I put away the Tandy Radio Shack system, with its cassette deck data storage and lack of mouse or any other input than a keyboard, and embraced the new IBM PC. It had no hard disk, so there was a lot of swapping in-and-out of those floppy disks just to get anything done. One disk held the software, and another the data being manipulated, but some programs required a second or third disk to be switched out to complete certain program functions. Smooth and seamless it was not.

The system John received came with several pieces of software, including PeachText, an early word processing software, PeachCalc for spreadsheets, and DBase II, software that finally improved the processing of all of the survey responses I was collecting. I was thrilled to have all these new capabilities. I believe the state of Georgia might have been involved with all that peachware. It was at this time that I got a lot better at what was to become a bit of a specialty in my later career; moving information from one format or system to another. The survey responses were in a dBase database, and I wrestled them over to PeachCalc for the tables and bar charts, mixing all of this with the PeachText. It was quite a wrestling match!

Meanwhile, things back in Texas were starting to get interesting. Phone calls were short and terse and I was clearly still in the dog house. One day a friend in the Marine Research Lab called me up to let me know that no one appeared to be staying in our apartment, the married student housing we had finally secured. Later, word came that my wife had been seen stepping out with a young man. They were spotted going to church one Sunday. After years of tension, I have to admit to not being concerned.

It all came to a head one day when I got a call from my spouse, asking why I never took HER to church. When we had been married, the preacher had asked us about our religious affiliation. My mother raised us in the Congregational Church, but I finally explained to him that in truth, I was a Pantheistic Agnostic. He paused for a moment, and then looked at the two of us. “I get the Agnostic part, but Pantheist? You believe that God lives in rocks and trees?”

I looked at him and said “Do you believe that if she wanted to live in a rock, she couldn’t?” That was pretty much the end of the religious discussion within our new family, and it was clearly coming back to haunt me. I was living at the largest outdoor temple in the world, and I worshiped her creation every time I stepped to the Rim. I was religious, but worshiping indoors was not my preferred form.

In our best times everything turns into religion, all the world seems a church and the mountains altars.

John Muir, My First Summer in the Sierra

She told me “I want a divorce.” I told her to send the papers and I would sign them. She said she wanted to discuss it some more, at which point I am afraid I said “There is nothing left to discuss. Send the papers, and I will sign them.” And I did.

They set the IBM Personal Computer up in a broom closet, and I swiftly became the primary user. With John in the hospital, I had a distinct advantage. It was an improvement over sitting in the hallway, and it almost felt like my own private office, although it was cozy. They had at least taken the brooms out.

I went back years later to take a look at the old office at the back of the clinic. Overrun with Rangers now, which actually made a lot more sense given their Emergency Medical role and their need to work closely with medical staff at the clinic, I could find no trace of my broom closet. The space inside the building had been substantially altered. It was 40 years later, after all.

At the time, I quickly absorbed all of the software manuals and harnessed the PC to work on my project. I entered all of the responses from the surveys into the system, and began doing some number crunching into tables. I took the text and started typing it into PeachText. Man, this was living, and I felt no regret as the typewriter collected dust on the table in the hall.

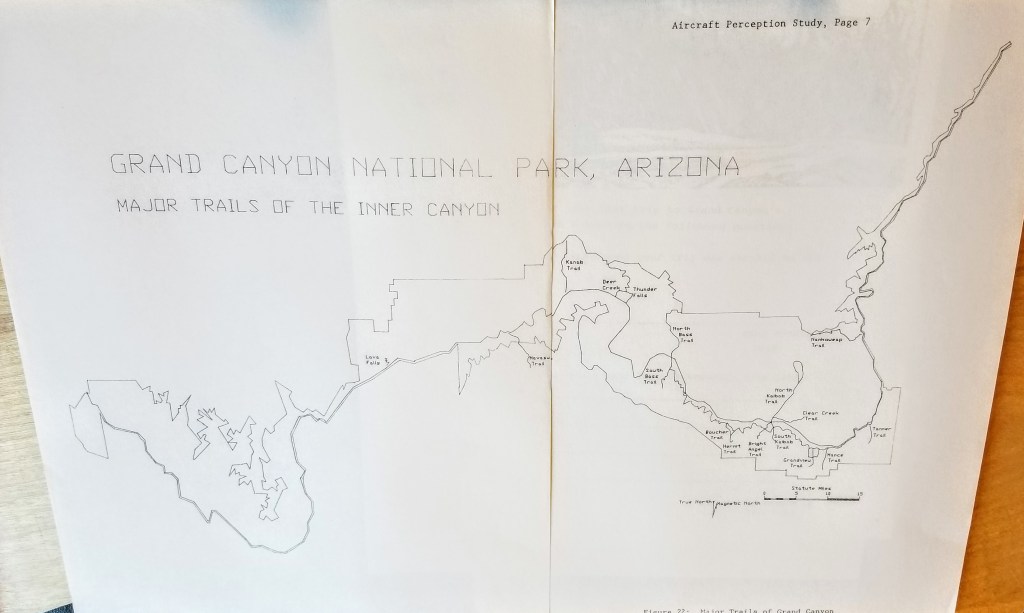

One of the software packages that I had the most fun with, by far, was AutoCAD. This drafting software allowed one to enter points, lines and a few other basic shapes including labels. I wanted to feed a map of the Grand Canyon into the software, but the only way I could figure out to accomplish this was by taking a map, tracing the outlines on a piece of clear plastic, putting that plastic up against the screen of the monitor, and tracing along the lines with the mouse and a WHOLE LOT of clicks. It was time consuming and tedious and it took a lot of work to go all the way around the park, but I eventually succeeded.

I’d also started tracing in the major trails, the Colorado River, and finally the South Rim Village. I decided to make a larger map of the Village as well. I was almost having too much fun. People started noticing all the activity in the broom closet, and suddenly there was an interest in doing a lot more with the basics I had explored.

The archeology team wanted to map some of the many sites they had identified, and were excited that they could code into the database a series of attributes for each point, but when I pointed out that the mapping system was none too accurate, they weren’t fazed at all. “We really don’t want to be too accurate. We do want to be able to capture and catalog the attributes of these sites, but we don’t want to steer in the pot hunters.” At the risk of losing my virtual monopoly on the one computer in the office, I said “You’ve got a system that will work for that,” and showed them how to code in and drop the locations onto the map I had compiled.

I was fortunate that most of them still preferred to spend their time out in the field – or perhaps felt sitting in a broom closet beneath their dignity.

Eventually I had most of my survey data entered into the system, and could display tables with percentages. Surveys kept trickling in, so there were always a few more responses to enter, including the comments they had provided. I painstakingly typed them into a long list, which was one of the more interesting pieces of the report. That compendium is included at the end of this book.

At one point, I thought about all of the various hikes completed below the Rim. After some rough calculations, I came up with the figure; over 300 miles of hiking throughout the backcountry. I have been blessed to add a few more since completion of the project, and each opportunity is a glorious time.

I had all but the final text written, and the floppy disks were piling up. Like the archaeologists, though, I wanted to be back out in the field, and John, apparently fully recovered from surgery (which, as he described it, sounded truly horrifying) was willing to oblige.