One day, my friend Dave came and told me there was a dance the next day; was I interested in going along? He clarified that it was a dance at Third Mesa, one of the smaller Hopi villages out on the reservation. The Hopi performed elaborate religious rituals, and the opportunity to see one was one I could not refuse.

We woke up well before dawn for the long drive out to the Reservation, and I was sleepy but excited. We drove along the South Rim down to Desert View, a spectacular tower that was one of the legacy structures from the Park Service’s early presence at Grand Canyon. Leaving the park, we swung past the small jewelry and rug stands that line the road near the edge of the Park and out across the Painted Desert. Beautiful and more than a bit desolate, the landscape stretched on for many miles.

A pallet of sand, so many hues so exposed by the heat and the arid climate. Parched, water nowhere much, except for the Colorado and the Little Colorado, a tributary that stretched up into the Reservation. Small streambeds fed down from the plateau, dry washes for most of the year. They were dangerous places to be after a cloudburst.

The land east of the Park is reservation land for two very distinct tribes. Most of the land, and many of the sheep, belong to the Navajo. They are a proud tribe with a rich history reaching back before the first European settlers arrived at Jamestown. One of their proudest moments was during World War II, when they were recruited to serve in the Pacific. Operating the radios, they were speaking in code but also in the Navajo language, totally baffling all Japanese attempts to discover what was being said. Years later, I was fortunate to meet some of the code talkers in Santa Fe, and offer personal thanks.

Within the Navajo Reservation, the Hopi strive to maintain their own unique culture and traditions. They had sought high ground, and their villages stretch across several mesas, cultural islands in the middle of the dry sea of the sparsely populated Navajo Nation.

Finally, we arrived at the village of Old Oraibi, which was said to have been established in 1100 A.D.; the “oldest continuously inhabited settlement in North America.”* I’ll have to take their word for it. The village was a fantastic layer cake of adobe construction perched on top of a sinuous mesa, as advertised. A steep road climbed around the hill and an early morning bustling atmosphere was just starting to get underway. Dave, his wife, and I were three of just a few of the non-Hopi spectators hoping to enjoy the scene.

If you wanted to be windswept, this was your place.

There is no filming of the dances. There is no painting, sketching, or recording of the dances. You are to sit and watch, and absorb it. it definitely felt like we were fortunate yet not entirely welcome guests.

Dave led the way, an old hand at attending these dances. He took us up some steep adobe steps to the roof of one of the low buildings that lined a substantial courtyard at the center of the mesa village. Other buildings also held a scattering of spectators, but most of the village stood around the courtyard, waiting for things to kick off. We spread a blanket and sat, sipping water (no alcohol allowed) and watched the sun as it started to rise higher in the sky. I remember being glad they had counseled me to bring sunscreen. The shade was scarce.

In the center of the courtyard was a domed Kiva, the ceremonial and spiritual center of the Hopi community. The door was shut, but wisps of smoke may have been emerging through the central roof. I truly don’t remember, but I would have expected it.

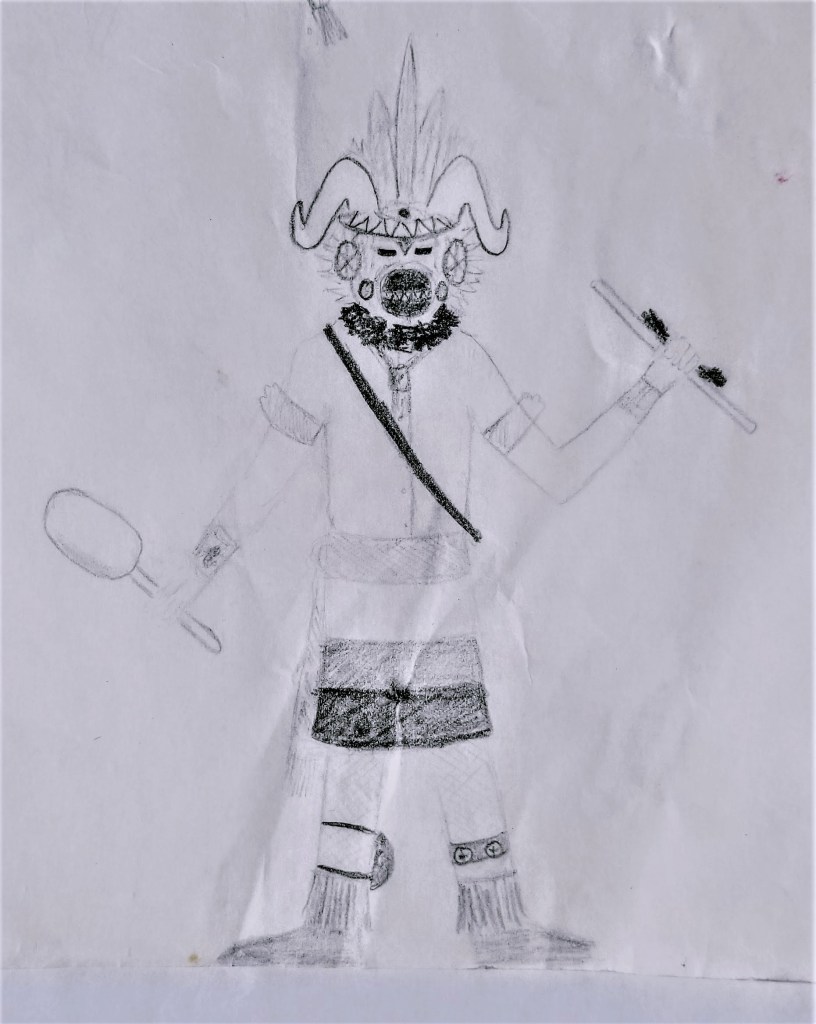

All of a sudden, the Kiva door opened and the village began to buzz as the dancers emerged. They lived up to the pre-dance hopes, elaborately dressed in large and I am sure heavy full head covers. They were all roughly the same, with large ram’s horn spirals on each side and a collar of juniper branches. Large black slits for eyes. Strange black beaks lined with sharp teeth. Feathers protruding from their heads and long shafts they waved about. Silver and turquoise highlights. A thick brim across the forehead. Fantastic!

Decorations wrapped around their wrists, chest and ankles. A turtle shell rattle was in constant motion, strapped to the calf of one leg. They were the living deities portrayed in the beautiful and often very expensive Kachina dolls of the area – and though I have looked for the particular costume I saw in many shop windows and display cases, I have not yet seen a really good match.

The image linked here by the Hopi artist Raymond Naha is the closest approximation I have ever seen of what I witnessed that day, and better than my sketch from memory.

I sat in wonder. There must have been at least fifteen or twenty dancers, all with this elaborate costume. And there were many dances during the course of the year, each with its own costumes and rituals. I had visions of a large hall lined with the head coverings, all staring out from shelves.

Of course, for the Hopi, there was no such image. These dancers were gods, emerging from the Kiva after cleansing rituals and then returning to their sacred homes once the dance was complete, waiting for the dance the next year. The idea that these were fathers, uncles, or cousins in costume were probably not thoughts any of the younger Hopi ever expressed.

They seemed to dance tirelessly under the sun, now really getting started in the Arizona sky. They paraded, stomped, chanted, and worshiped below us, and the Hopi that lined the courtyard walls seemed caught up in the ritual. Rattles scratched out their rhythm, seemingly encouraging the dancers to move with greater energy.

At some point, the dancers decided to once more retreat into the Kiva, and out came the Kosharis, or clowns. Clowns are very much a part of the Hopi tradition, and these white and black striped characters with their long tessellated horns (in matching stripes) took over the courtyard dance floor, teasing the audience, making faces at the children, knocking each other about in mock fights and much ribald carryings-on. After the solemnity of the ram dancers, these clowns provided a wonderful relief. We watched from above as they worked the crowd. They seemed to know everyone there except us tourists peering down from the roofs.

Eventually, the clowns slipped away and the ram dancers returned. Rested, perhaps, they continued the dance and then began assembling large bags full of food. They began to distribute the food to the crowd. It was my impression that they, too, knew everyone in the village, and who might have been hungry or in need. They carefully pressed loaves of bread and other items into the hands of the crowd, but it seemed that a smaller, older subset got the best of the distribution. I realized that this was one way the community saw to it that those who were in most need had those needs met. It was a very moving scene.

After a long day on that roof, and a picnic lunch we had packed the day before (there was no store or food distribution to the non-Hopi spectators) we headed back to the small truck and began the long drive home. I was very grateful to Dave and his wife for sharing that incredible experience with me. Living Kachina!

When I got back to the trailer that night, I sat down and sketched out a ram dancer. I had tried to remember every detail of their incredible costume. I rediscovered it the other day; the headdress is above. I will never ever forget that day!

The black-and-white figures are Kosharis, or Hopi clowns.